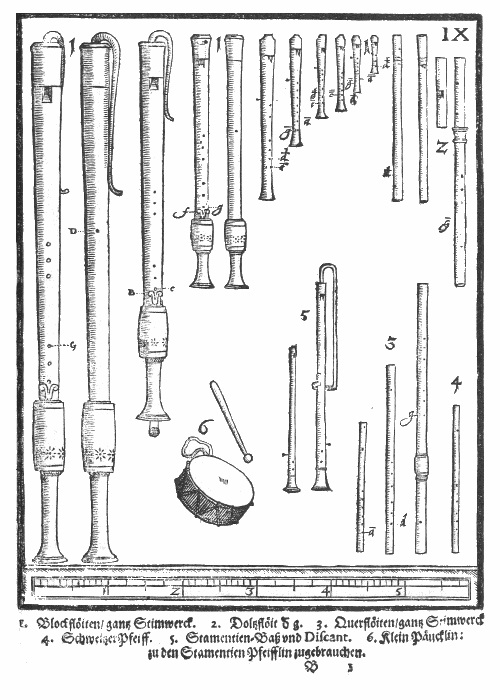

On the other hand, in the introductory section "Renaissance Flute in Context - Past and Present" of the instructional book "The Renaissance Flute / A Contemporary Guide" co-authored by Kate Clark and Amanda Markwick (published by Oxford University Press), it is stated: "It is clear from these sources that the flute, throughout the sixteenth century and well into the seventeenth century, was conceived of as a consort instrument. In other words, flutes were made in "families" consisting of three different lengths: the bass flute in G, the tenor / alto flute in D, and the soprano flute mostly in A, though there is some evidence that at least by the turn of the seventeenth century, the somallest flutes could also be made in G. Throughout the same period, violins, viola da gamba, recorders, lutes, and other instruments were likewise made in sets or families."

In this way, the enigma arises whether the discant Renaissance Flute is in A or G, or perhaps both.

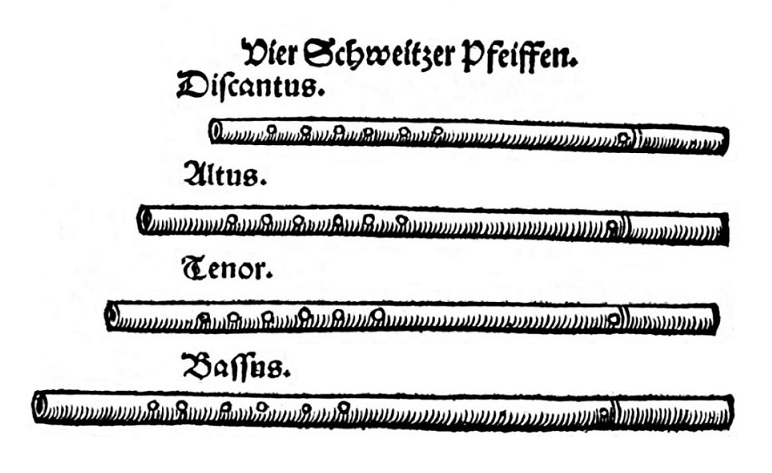

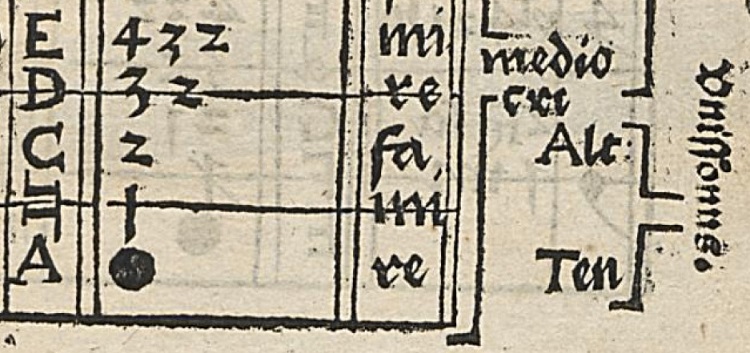

Now, going back about a century from the publication of 'Syntagma Musicum' in 1619, we find 'Musica instrumentalis deudsch' published in Germany in 1529. Written by music theorist and composer Martin Agricola (1486-1556), the diagram in the image above is from this work, titled "Dier Schweitzer Pfeiffen." It labels the longer (lower-pitched) pipes as Bassus, Tenor, Altus, and Discantus.

By deducing from the description by Clark and Markwick, it seems reasonable to consider that the low-range bass is in G, followed by the tenor in D, the alto in A, and the highest-pitched discant in G. Therefore, let's position this as the "Hypothesis of Swiss Flute"

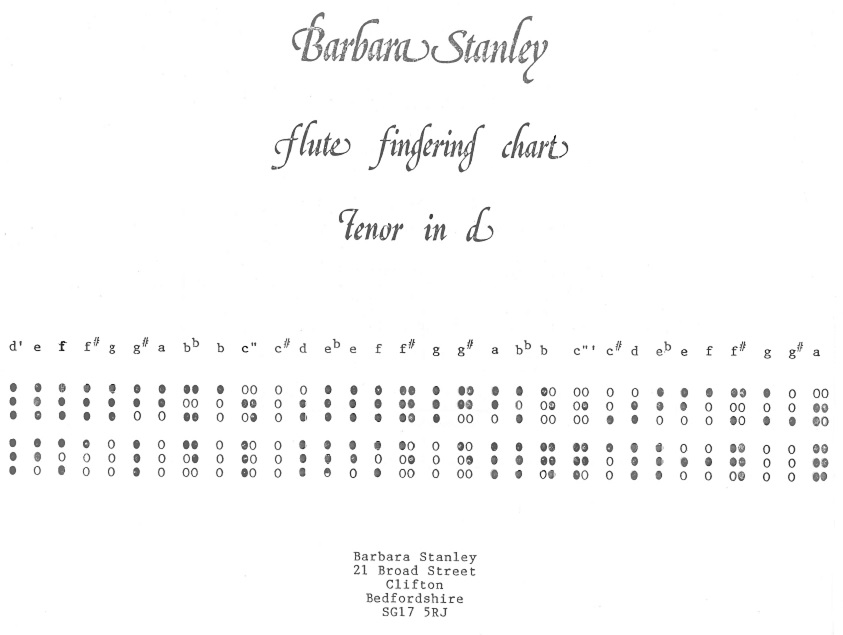

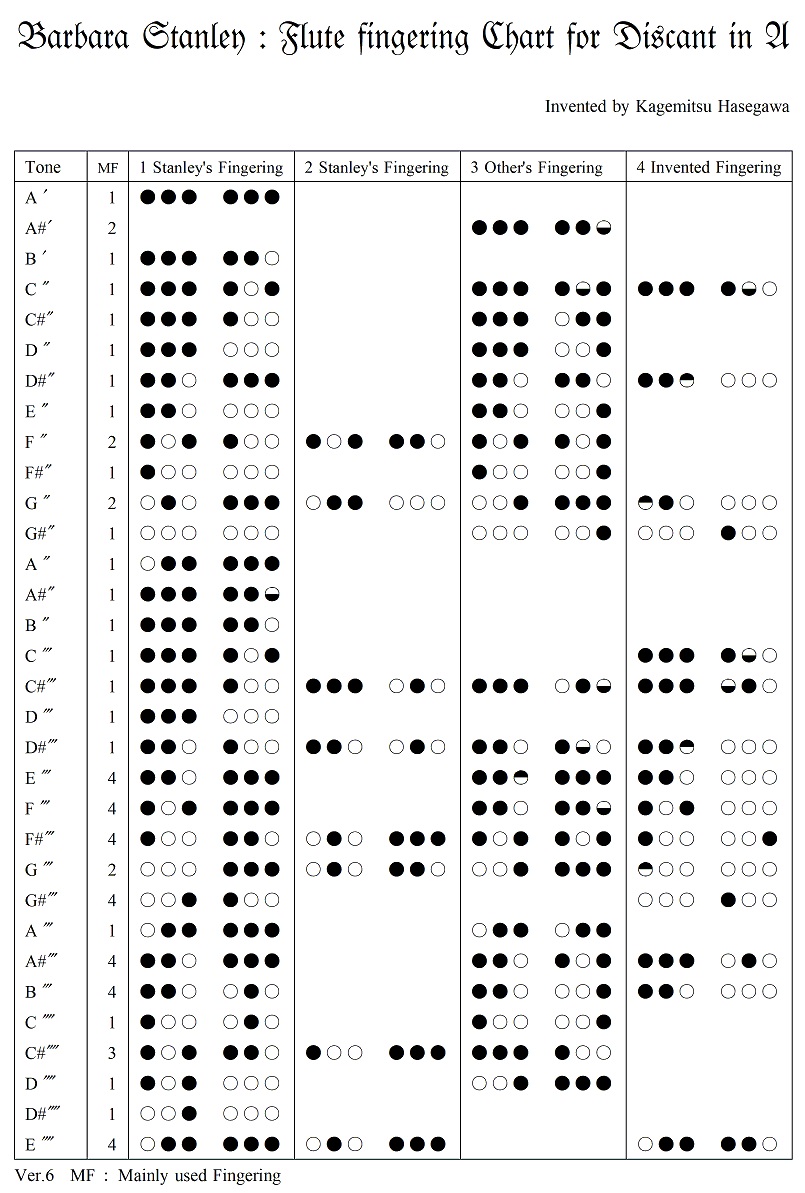

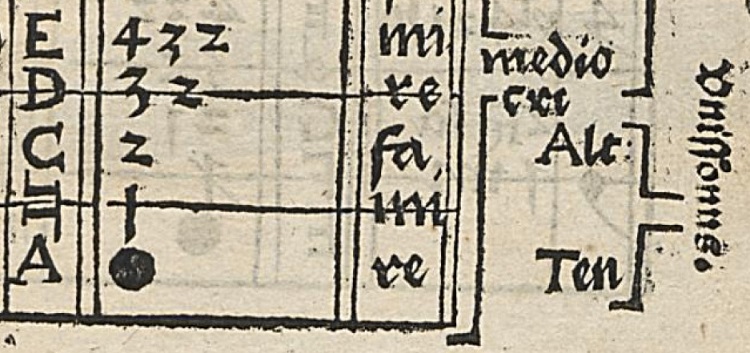

'Musica instrumentalis deudsch' provides tuning, fingering, and the speed

of breath needed for each Renaissance Flute, indicating that the bass is

in D, the discant in E, and as seen in the image below, the tenor and alto

are marked as Unissonus, and only A is mentioned.

This diagram has been the cause of misunderstandings for centuries. Therefore,

both Maeda, Clark and Markwick likely identify D as the tenor / alto. However,

in the diagram of "Dier Schweitzer Pfeiffen" the alto is depicted

slightly shorter than the tenor, and theoretically, it cannot be said that

the tenor and alto are in unison.

Firstly, on the right side of this diagram, both for the bass on page 1, the tenor / alto on page 2, and the discant on page 3, "Vent" or "breath expulsion" is written. On the left side, as indicated in the above diagram, it instructs to blow at a mundane or ordinary speed, denoted by "mediocri."

In that case, since there is an abbreviation for Ten and Alt in the breath expulsion and speed instructions, the fact that A and D are connected by a line has a special meaning.

And, the last issue is the word "Unissonus" but I realized that this does not mean unison, i.e., the same note. Since the Latin word "Unissonus" means "Oneness" or "Harmony," interpreting it as the latter harmony, A and D are in a perfect fourth relationship, precisely forming a harmonious interval.

Based on these considerations, I concluded that the tenor is in A pitch, and the alto is in D pitch in this book. As a result, the tenor's A pitch is five degrees higher than the bass's D pitch. The alto's D pitch is four degrees higher than the tenor's A pitch. And the discant's E pitch is two degrees higher than the alto's, leading to my own perspective.

Even if this interpretation is incorrect, the Renaissance flute transitioned from four pipes to three pipes during the last century or so. If this description is correct, it would mean a significant change in tuning.

Furthermore, Maeda states in the previously mentioned book's section on "Existing Renaissance Flutes" as follows: "There are only about 45 surviving Renaissance flutes in the world today. They come in various lengths, ranging from about 30 cm to 90 cm, but can be broadly categorized into three sizes: discant, tenor, and bass. Unfortunately, there is only one discant flute remaining in the museum in Brussels, and even that instrument may have been made in the 19th century. Moreover, it is currently missing, so its authenticity remains uncertain." (PP36-37)

Thus, not only is there a lack of existing discant Renaissance flutes from that time, but there are discrepancies in the pitch as well. In "Musica instrumentalis deudsch" it's an E pipe, in "Syntagma Musicum" it's an A pipe, and in the "Hypothesis of Swiss Flute" it's a G pipe, deepening the enigma.

By the way, Clark and Markwick, on the website "Renaissance and Baroque Musical Instruments" in an article titled "An Introduction to the Renaissance Flute" writes the following: "The tenor renaissance flute in D is the most versatile, as it is able to cover the soprano, alto, and tenor ranges of nearly any 16th-century piece of music. A bass flute in G completes the flute consort, although adding the bright color of a descant flute(My note: Same as discant flute) in A or in G can really contribute to a jovial character (especially nice in dance music, or light-hearted chansons, for example).

If it is an "A or G discant flute" it aligns with both "Syntagma Musicum" and the "Hypothesis of Swiss Flute"

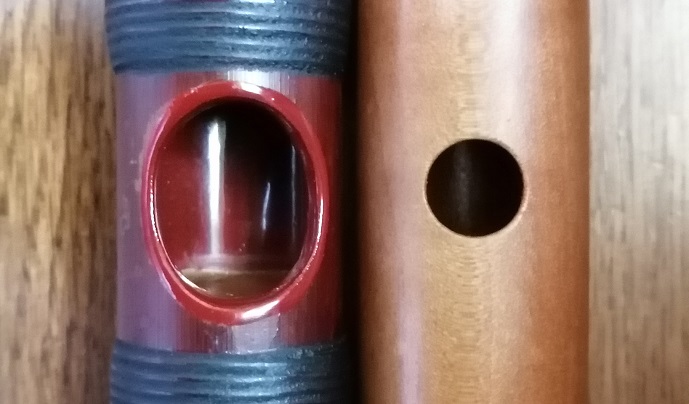

Now, in contemporary Germany, Christoph Hammann's work categorizes the

Renaissance flute, with the soprano in D and the alto in G, as shown in

the attached picture. |